UPDATED MAY 21, 2018

The most recent Worms & Germs Blog on canine influenza states that no new cases were identified in Ontario in April and May. This means that there is no longer a threat of spread from the cases introduced into the province earlier this year. Canine influenza has therefore been eradicated from Canada, at least for the time being. The risk of re-introduction from sources outside of Canada remains quite high, given the ongoing presence of the virus in the USA and its endemic nature in other parts of the world.

Source: Veterinary Team Brief

Quick Q&A:

Should shelters be vaccinating? Given that the immediate threat is now gone, there is only a weak case to be made for vaccination and the general answer is now “No”. For shelters and rescues with the resources and with long stay canine populations, vaccination could be considered, given that it’s probably only a matter of time before the virus pops up again.

What vaccine is available? The Nobivac (Merck) bivalent killed vaccine.

What is the best diagnostic test? PCR using deep nasal and pharyngeal swabs. Active surveillance remains very important, as does isolation of dogs from high-risk locations.

CIV vaccination

The Nobivac (Merck) vaccine is currently available in Canada.

This is a killed, bivalent H3N2/H3N8 vaccine. Two doses are required a minimum of 2 weeks apart, and immunity only develops 1-2 weeks after the SECOND dose. A single vaccine is not useful because this is a killed vaccine, so a booster is essential. Dogs can be vaccinated from 7 weeks of age. The immunity is non-sterilizing but the vaccine is expected to reduce the shedding time and protect against severe disease.

Should we vaccinate shelter dogs for CIV?

Given that the immediate threat is now gone, there is only a weak case to be made for vaccination and the general answer is now “No”. For shelters and rescues with the resources and with long stay canine populations, vaccination could be considered, given that it’s probably only a matter of time before the virus pops up again. Although the vaccine offers only partial immunity, we are dealing with a population that is completely naive to this virus.

Resources need to be balanced between risk assessment, quarantine, vaccination and testing.

Should vaccines be offered at public vaccine clinics to create herd immunity?

There is no current recommendation to this effect.

Testing

What screening tests and active surveillance are recommended?

Tests are expensive, so to get the most bang for your buck, use the highest value tests in the animals most likely to provide a useful result. Active surveillance is recommended for animals from a high-risk source. Testing several animals is more useful than testing only one, but there is no need to test every animal. If one animal tests positive, the whole cohort must be quarantined, and all symptomatic dogs in the cohort would be presumed to have influenza, so testing every dog is not cost-effective.

The dogs that should be tested are the most acute cases – dogs that are just starting with clinical signs, such as reduced appetite and fever. Testing healthy dogs in case they are shedding isn’t cost-effective.

Dr. Scott Weese recommends the PCR test for canine influenza. This is offered by IDEXX, Antech and AHL. Respiratory virus panels are preferable, because coinfections are common and have implications for severity and management. The PCR test will remain positive longer for H3N2 because of the long shedding period, whereas it can become negative quite quickly after H3N8 infection. Deep nasal and/or pharyngeal swabs are recommended.

Can samples be pooled to save money?

Maybe, but this could reduce sensitivity. It’s better to sample dogs individually and select the cases most likely to give a diagnostic result.

What should shelters do if we identify a case?

Animal influenza is reportable in Canada, so the local public health unit must be informed. Expert advice on dealing with new cases can be obtained from shelter medicine and infectious disease specialists. It might also be helpful to contact diagnostic laboratories or vaccine manufacturers, who might be willing to help with testing and vaccination costs.Merck currently offers a testing program for shelters, however, prior approval before you initiate testing is required as there are specific criteria that need to be met to qualify.

Preventing and Managing Outbreaks in Shelters

What’s the most important thing to do?

Minimize risk and be prepared in the event of outbreaks. Develop, or review and revise, transport/importation, disease surveillance and outbreak prevention/management protocols.

Minimizing the risk of importing canine influenza

- Before bringing dogs in, ensure that your shelter has the knowledge and resources to manage imported infectious diseases. We might be worried about H3N2 now, but there are multiple potential risks. The Report of the Canadian National Canine Importation Working Group (even if you only have time to read the Executive Summary and list of diseases of concern) is a great resource for developing broad-based preventive and containment strategies.

- Identify and minimize known risks in advance of importation. Canine influenza is endemic in Thailand, South Korea and China, and can essentially be considered endemic in the USA. Northern California and Nevada continue to be “hot spots” and the virus has popped up in other new locations in the US. For maps, see the Worm and Germs blog.

Recognition

Canine influenza is clinically indistinguishable from other canine respiratory infections. Clinically it can range from mild to severe disease, with severe disease more likely to occur in juvenile, naïve and stressed animals, and in conjunction with co-infections.

Incubation and shedding

The incubation period is typically only 2-4 days. Dogs can shed large amounts of virus for a day or two before showing clinical signs. For H3N8, shedding after illness is a week or less. H3N2 typically has a shedding period of 2-3 weeks and in some cases up to 28 days. This makes it higher risk for spreading.

What precautions should Canadian shelters take with imported dogs?

The first step is risk analysis. The more you can find out about the source of the dogs, the better. For example, the US is considered endemic for canine influenza but the risk is very different in different geographic areas. Obviously, the higher the known risk, the more precautions are needed. Avoiding high-risk imports is the ideal solution, but this isn’t always possible.

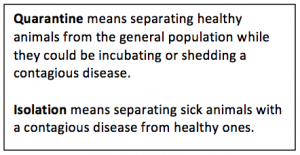

The highest value period for quarantine is the first 7 days, so this should be considered the minimum for all imported dogs. If there is known infection or high risk of H3N2, dogs should be quarantined for 3-4 weeks (this is recommended even if they show no clinical signs, because of subclinical infection or illness before transport). Quarantine should include keeping the dogs in a closed group (cohort) and using gloves and gowns when handling, as well as being careful to avoid fomite transmission via leashes, toys or food bowls.

Direct contact and fomites carried on hands are the most important means of transmission, so focus most effort here.

Should dogs be available for adoption while in quarantine?

Open selection is advised for healthy dogs – in other words, adopters should be able to view the dogs, or information about them, and preselect them for adoption. As to whether healthy dogs should be released to their new homes within the quarantine period, that would depend on the local risk. Reducing length of stay is always preferred where possible, but that has to be balanced against the risk of introducing a new disease into a community, something no shelter wants to be remembered for!

The quarantine period should end when the last symptomatic animal in the group reaches the end of its potential shedding period. , so this is a minimum recommended period. The duration of quarantine should be risk-based.

If a shelter or practice provides services for dogs from other shelters or rescues, what precautions should they take to avoid influenza?

If the dogs are from a high-risk area, it would be prudent to wait 28 days from their date of importation, or from the last day of clinical signs in the group, before bringing them in to a facility.

More CIV Information

H-what?

The two canine strains are H3N8 and H3N2. In the USA, H3N8 was first identified in 2004, and H3N2 in 2015. This map shows how the viruses have spread across the USA; and this one shows the prevalence of the viruses. So far, H3N8 has not been identified in Canada. The current threat is from H3N2.

Is canine influenza zoonotic?

No (with the caveat that in biology, as in US Presidential politics, it’s unwise to use the words “never” or “impossible”). The dog would have to be simultaneously infected with a canine virus and a human virus, they would need to recombine and only then could the virus could jump to people – so the likelihood is exceptionally small. No cases of canine influenza have been reported in people to date.

How long does the virus persist in the environment?

Influenza only persists for a few days in the environment and is killed by routine disinfectants.

What is a good CIV resource for owners?

Shorter: AVMA information page

Longer: AKC information sheet

References:

1. Worms and Germs blog

2. Cornell Canine Influenza H3N2 Updates and Maps

3. AVMA Canine Influenza resources

4. CVMA Position Statement on Importation of Dogs into Canada

5.Report of the Canadian National Canine Importation Working Group (2016)

6. VetGirl Webinars: Updates in Canine Influenza Virus: Management, Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention and Vaccination (2017) and NEW, FREE webinar, Canine Infectious Respiratory Disease Complex: 2018 Update on Canine Influenza and Bordetella