By Dr. Tracy Satchell

For many pets across the world, access to veterinary care is a luxury. A 2018 study by the Access to Veterinary Care Coalition found that over 25% of US pet owners are unable to afford basic veterinary care, such as vaccinations, parasite control, and spay/neuter [1]. In this same study, the authors surveyed US veterinarians about their attitudes regarding providing veterinary care to pets from families of all income levels. While the large majority (94.9%) of US veterinarians believe that all pets deserve some level of veterinary care, they did not feel it was society’s responsibility to provide this care should the owner not have the financial means.

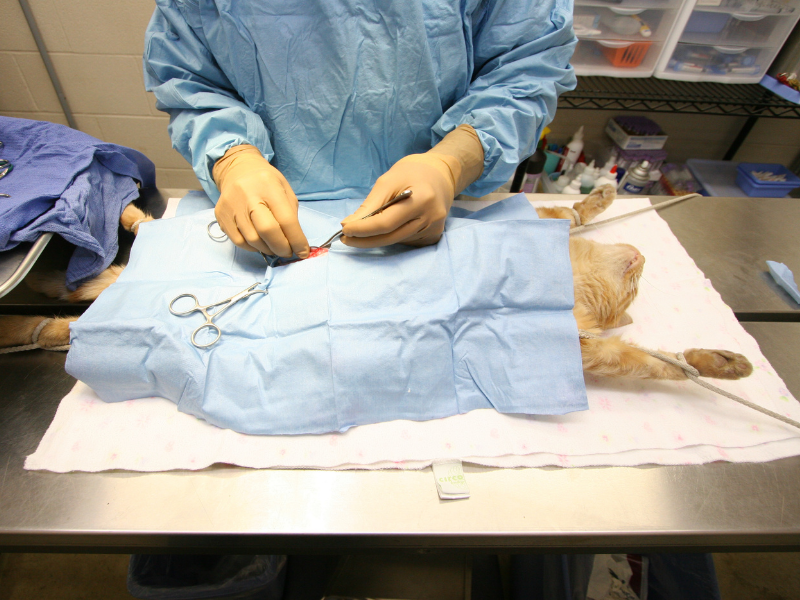

Published in the Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery (2020), Bushby’s article explores the link between accessible veterinary care, the rise of popularity of high-quality, high-volume spay/neuter (HQHVSN) clinics, and the challenges that this poses for private practitioners.

The Emergence of spay/neuter clinics

As early as 1970, the City of Los Angeles in California began to open high-volume spay/neuter clinics in animal shelters to combat the overpopulation of dogs and cats [2]. This was at a time when surgically altering a pet was rare, and only about10% of pet dogs and 1% of pet cats were sterilized, leading to over 20 million shelter animals being euthanized each year. The government-funded clinics enraged the local veterinarians who saw these clinics as unfair competition. In response, these local veterinarians opened their own low-cost spay/neuter clinic and employed Dr. Marvin Mackie, who is recognized as the first ever high-volume spay/neuter surgeon.

Attitudes about spay/neuter have gradually shifted as the public has become more aware of pet overpopulation. Most pet cats and dogs are now spayed or neutered, and many animal shelters only adopt out already altered animals. HQHVSN clinics have been established throughout the US and Canada and the number of animals euthanized in US shelters has been reduced to the current estimate of 1.5 million [3]

Concerns regarding HQHVSN

Despite the impact on shelter euthanasia rates, high-quality, high-volume spay/neuter (HQHVSN) clinics continue to be controversial among the profession. Some private practice veterinarians believe that these facilities ‘steal their clients’ and others feel that HQHVSN clinics do not meet professional standards. These two concerns are readily addressed.

While there is very little data on the impact that HQHVSN clinics have on the local private practice veterinarians, spay/neuter clinics are appear to be meeting the needs of an underserved demographic. A 2016 study found that most of the cats sterilized in a

Massachusetts, USA, low-cost spay/neuter program had not seen a veterinarian because the cost of care was too expensive [4]. Many of these people cannot and will never be able to afford private practice prices– these clients cannot be stolen if they were never going to be a client in the first place.

In 2016, the Association of Shelter Veterinarians published updated medical care guidelines for spay/neuter clinics in an effort to ensure that HQHVSN clinics were delivering high-quality care in the high-volume model. In one study, over a period of 7 years, one large HQHVSN clinic in Florida documented mortality rates approximately 1/10th of those at private practices [5]. Bushby explains why HQHVSN clinics can have such dramatically low mortality rates, “Simply put, adhering to basic principles and performing the same procedure repeatedly, increases efficiency, improves quality and reduces complications.”

Basic Principles for Efficient Spay/Neuter

HQHVSN clinics are able to charge less per procedure because they are quick and efficient at sterilizing animals.

Bushby describes three key principles in developing efficiency in spay/neuter surgery: blocking off a designated surgery time, performing surgeries at a younger age, and adopting efficient surgical techniques.

1. Designate a block of time specifically for spay/neuter surgeries.

The goal is to minimize the amount of time between one surgery and the next so that the surgeon can complete one surgery, re-glove, and start the next surgery without delay. The surgeon should not be disturbed and allowed to focus on only surgery during this time – no interruptions about Mrs. Smith’s recheck appointment or the whereabouts of more printer paper.

2. Perform surgery on cats prior to 5 months of age.

Spaying cats before 5 months of age is easier, faster, and leads to fewer complications [6].

3. Adopting efficient surgical techniques.

Many of the techniques that are taught in veterinary school can be replaced by ones that are safer and more efficient.

When positioning a cat spay, do not tie the forelimbs forward as this can make the ovaries more difficult to exteriorize.

- For cat castrations, placing the cat in dorsal recumbency with the rear limbs pulled forward provides easy access to the scrotum.

- Cat spay incisions should be made midway between the brim of the pelvis and the umbilicus, and 1-2cm in length.

- Use a spay hook to locate and exteriorize the uterus. The ASPCA has a video detailing this technique at aspcapro.org/resource/how-use-spay-hook-surgery

- Clamp the proper ligament with a hemostat to assist with exteriorizing the ovary and cut the suspensory ligament with a scalpel or scissors.

- Instead of ligating, use the pedicle tie to self-ligate the ovarian vessels in the cat. This technique is fast and safe, even for pregnant cats or those in heat.

- Without clamping, use a modified Millers knot to ligate the body of the uterus for cat and dog spays.

- For routine cat spays, closure of the abdominal wall can be accomplished with one or two cruciate sutures and the skin closed with one or two simple interrupted subcuticular sutures.

- Place a small scoring tattoo with green ink near the incision for cat spays, or close to the umbilicus for cat neuters. Ear-tip the left ear of feral cats or those cats that will be released back outside.

Videos of many of the above techniques are available in the supplementary materials of this article. If you are Guelph Alumni, you can access this full-text article via your Alumni Library Privileges.

Supplementary materials:

1. Wiltzius, A. J., Blackwell, M. J., Krebsbach, S. B., et al. (2018). Access to Veterinary Care: Barriers, Current Practices, and Public Policy.

2. Bushby, P. A. (2020). High-quality, high-volume spay–neuter: Access to care and the challenge to private practitioners. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery, 22(3), 208-215.

3. ASPCA (n.d.). Shelter Intake and Surrender. Accessible at: https://www.aspca.org/animal-homelessness/shelter-intake-and-surrender

4. Benka, V. A., & McCobb, E. (2016). Characteristics of cats sterilized through a subsidized, reduced-cost spay-neuter program in Massachusetts and of owners who had cats sterilized through this program. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 249(5), 490-498.

5. Levy, J. K., Bard, K. M., Tucker, S. J., et al. (2017). Perioperative mortality in cats and dogs undergoing spay or castration at a high-volume clinic. The Veterinary Journal, 224, 11-15.

6. Land, T. D., & Wall, S. D. (2000). Survey of the Coalition of Spay/Neuter Veterinarians. Journal of American Veterinary Medical Association, 216(5).