Written by Dr. Anjali Narasimhan

Access to Veterinary Care and Public Health Considerations

Tuktoyaktuk is a northern Inuvialuit community located along the Arctic Ocean at the top of the Northwest Territories and is the northernmost community on mainland Canada (1). Geographic isolation shapes aspects of daily life, including access to veterinary services, as residents must travel extensive distances by road and, in some cases, air transport to obtain care, resulting in significant financial and logistical barriers. The nearest veterinary clinic is located in Dawson City, Yukon, approximately a 15-hour drive away, with additional hospitals located farther south in Whitehorse and Yellowknife. More complex cases requiring specialty services may necessitate travel to Vancouver, Calgary, or Edmonton. As a result, routine preventive care, emergency services, and ongoing animal health support are largely unavailable outside of intermittent outreach clinics. Tuktoyaktuk is also among the communities most impacted by climate change, with rapid permafrost thaw, coastal erosion, rising sea levels, and increasing storm activity affecting the area (2,3). These environmental changes have influenced wildlife movement patterns, including the population dynamics of Arctic foxes, with direct implications for both domestic animal and human health (4).

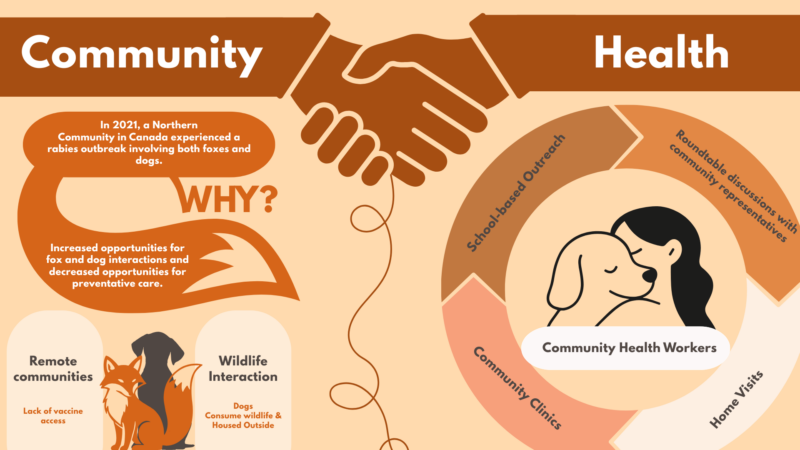

Rabies is endemic in the Arctic fox population of this region, and in 2021, Tuktoyaktuk experienced an outbreak involving both foxes and dogs that continues to shape community perceptions and response to this public health risk (4). To understand rabies in this context, it is important to consider the role of dogs in northern life. The relationship between Inuit communities and dogs is a longstanding partnership rooted in survival, culture, and companionship. In Tuktoyaktuk, dogs commonly serve as working animals used for sledding, hunting, and as early-warning systems for wildlife, such as polar bears, that may enter the community. Traditionally, dogs are housed outdoors and fed harvested “country food,” which includes fish, caribou, and other wildlife. These cultural and environmental factors influence dog management practices and patterns of exposure. In communities without consistent access to vaccination, spillover of rabies from wildlife into domestic dogs represents a significant zoonotic risk, positioning preventive veterinary care, particularly vaccination, as a critical public health intervention. In this context, improving access to preventive veterinary care requires approaches that extend beyond intermittent clinical services.

Vets Without Borders Northern Animal Health Initiative

The Northern Animal Health Initiative (NAHI), led by Veterinarians Without Borders North America (VWB), is one such model (5). In Tuktoyaktuk, this approach integrated open roundtable discussions with community representatives, including hamlet leadership, to identify local priorities around animal health; incorporated school-based outreach to promote youth engagement and rabies education; and delivered prevention-focused veterinary care through both community clinics and home visits to reduce barriers to accessing care within the community. A central component of NAHI is the training of Community Animal Health Workers (CAHW), community members who volunteer to receive specialized training and are equipped to support basic animal health and preventive care, including vaccination, animal handling, and first aid (5). The CAHW model emphasizes sustainable, culturally responsive, and community-led approaches that help bridge the gap between periodic community clinics and year-round animal health needs.

Training local vaccinators not only improves continuity of care but also strengthens trust in animal health initiatives. Community members are more likely to engage with programs led by familiar individuals who understand local realities and priorities, a principle consistently supported in community-based and participatory public health models (6,7). In rabies-endemic regions, this local capacity is particularly important for achieving and maintaining high levels of vaccine coverage. Sustained community-led vaccination efforts increase the likelihood of achieving herd immunity, defined as a 70% vaccination coverage in domestic dog populations to reduce transmission and interrupt rabies cycles, thereby supporting both animal and public health (8).

Reflections on Community-Based Veterinary Medicine

Veterinary medicine cannot be one-size-fits-all. Models of care developed in more urban settings do not always translate to northern or remote communities, where climate, infrastructure, cultural practices, and local capacity shape what care is both feasible and effective. Spectrum-of-care approaches grounded in prevention, flexibility, and collaboration provide a framework for delivering context-appropriate veterinary services while supporting both animal welfare and public health objectives. Aligning preventive health strategies with the lived realities of the communities they are designed to support is essential for delivering sustainable community-based veterinary care. When animal health programs are shaped and led in partnership with the communities they serve, they have the potential not only to improve animal welfare, but also to strengthen broader public health outcomes.

References:

(1) Northwest Territories Tourism. (n.d.). Tuktoyaktuk. Spectacular NWT. Retrieved January 22, 2026, from https://spectacularnwt.com/communities/western-arctic/tuktoyaktuk/

(2) Kidd, M. (2024, October 22). On shoreline disasters fast and slow. The Independent. https://theindependent.ca/commentary/on-shoreline-disasters-fast-and-slow/

(3) Government of Canada. (2020, July 10). Hamlet of Tuktoyaktuk: Climate change and coastal erosion. https://www.canada.ca/en/crown-indigenous-relations-northern-affairs/news/2020/07/hamlet-of-tuktoyaktuk-climate-change-and-coastal-erosion.html

(4) Simon, A., Tardy, O., Hurford, A., Lecomte, N., Bélanger, D., & Leighton, P. A. (2019). Dynamics and persistence of rabies in the Arctic. Polar Research, 38, 3366. https://doi.org/10.33265/polar.v38.3366

(5) Veterinarians Without Borders/Vétérinaires Sans Frontières Canada. (n.d.). Northern Canada: Northern Animal Health Initiative. https://www.vwb.org/site/north-america/northern-canada

(6) Rifkin, S. B. (2009). Lessons from community participation in health programmes: A review of the post Alma-Ata experience. International Health, 1(1), 31–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inhe.2009.02.001

(7) World Health Organization. (2016). Community engagement: A health promotion guide for universal health coverage in the hands of the people. World Health Organization.

(8) World Health Organization, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, & World Organisation for Animal Health. (2018). Zero by 30: The global strategic plan to end human deaths from dog-mediated rabies by 2030. World Health Organization.